By April Reese / Searchlight New Mexico

Dysfunction and a lack of expertise within the New Mexico Public Regulation Commission (PRC) threaten to undermine the state’s ambitious plan to flip the switch from coal to reenewable power.

The Energy Transition Act — the centerpiece of Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham’s agenda to rein in greenhouse gas emissions — phases out coal, turbocharges solar and wind development, and provides funding to retrain displaced coal plant and mine workers. It has been hailed as one of the strongest climate measures in the country.

But six months after Lujan Grisham signed the bill into law, its success appears jeopardized by the very regulatory body charged with overseeing its implementation.

The powerful commission must vet every aspect of the plan: the closure of the San Juan Generating Station coal plant; the complex financing to pay for decommissioning and worker assistance; and every new energy project that will provide the replacement power. But when the first proposals came before the PRC in July, the commission chose to ignore the new law, leaving the state’s energy transition in limbo.

The unusual move has sparked a political furor, pitting the PRC against the governor and Legislature and leading to calls for impeachment of three of the commissioners as well as a proposal by the governor to convert the PRC from an elected body to an appointed one.

The law’s supporters say the commission’s handling of the plan reflects deep dysfunction that could slow the state’s renewables ramp-up and jeopardize aid for displaced workers.

Lujan Grisham says she finds the PRC’s actions “baffling” and suspects that long-standing tensions between the commission and Public Service Co. of New Mexico (PNM), the Farmington-area plant’s majority owner and the largest utility in the state, may be clouding some commissioners’ judgment.

“I’m certainly not suggesting the PRC is just going to be wind advocates or align themselves with one company,” she says. “But they’re certainly making it harder for utilities to move in that direction …. I just don’t think that as a body they’re equipped to deal with a changing [energy] landscape. Many solar and wind companies are excited about the potential here, but if you have unpredictable regulators, you’re going to limit those opportunities.”

In addition to changing the commission to an appointed body (only 12 other states have elected utility commissioners), Lujan Grisham is calling for a reduction in their number from five to three. A similar proposal is set to go before voters in a November 2020 ballot measure, but Lujan Grisham doesn’t want to wait. She is pushing lawmakers to make the change as soon as the Legislature reconvenes in January.

One lawmaker has gone even further. Sen. Jacob Candelaria (D-Albuquerque) is calling for three of the five commissioners — Valerie Espinoza, Theresa Becenti-Aguilar and Jefferson Byrd — to be impeached.

“For all intents and purposes, they’re refusing to comply with the law, because they disagree with the law,” he says. “Espinoza, Becenti-Aguilar and Byrd have repeatedly rejected requests to explain their actions.”

Feeling the heat

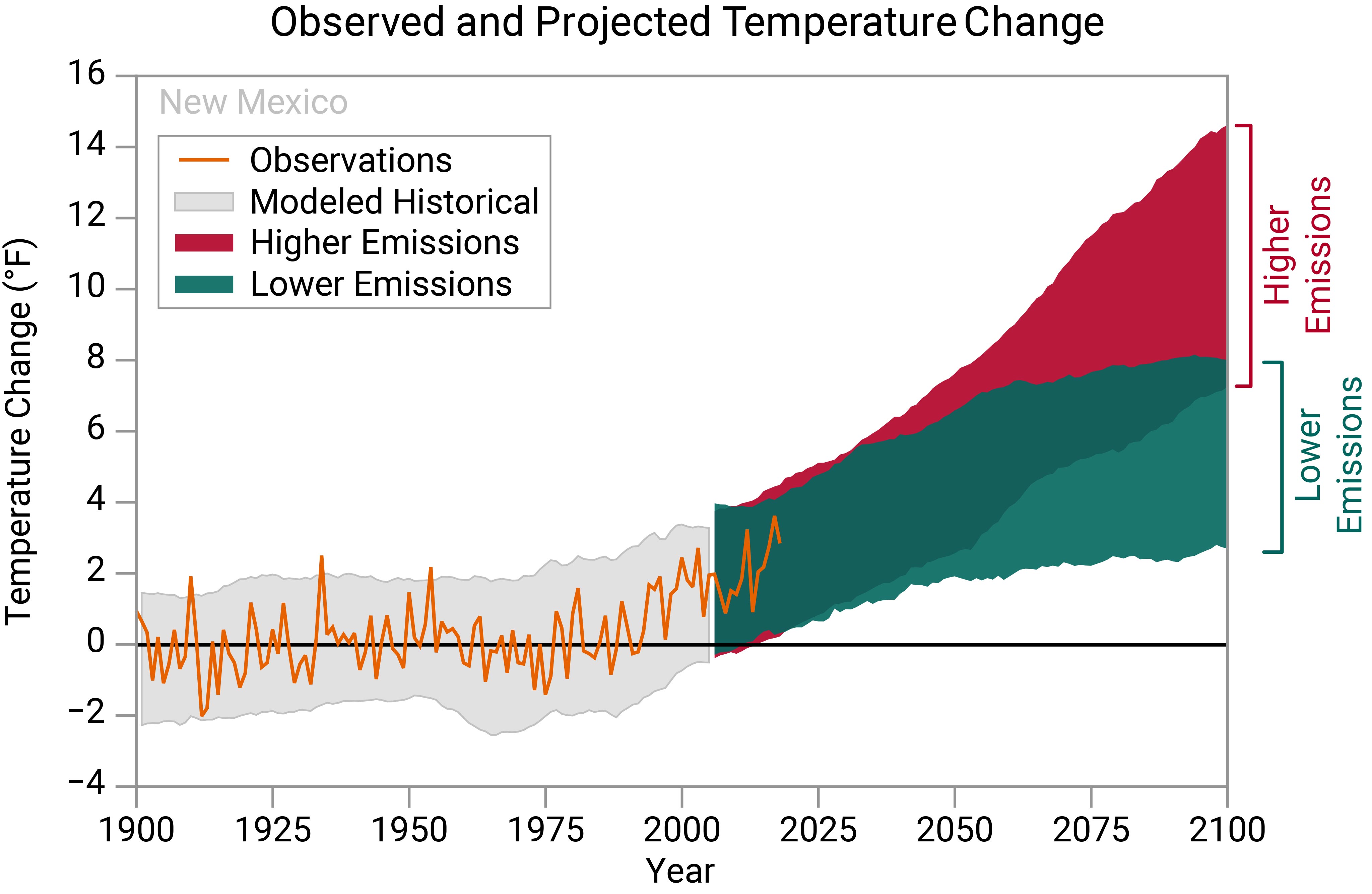

New Mexico, the second fastest-warming state in the U.S., is already feeling the effects of climate change: more severe droughts, more frequent heat waves, more large wildfires,. The ETA aims to steer the electricity grid away from coal, which currently makes up more than half of New Mexico’s energy mix. By 2050, the grid will be 100 percent carbon-free — if the law is adequately implemented.

Closing the coal plant, which emits 6,000,000 metric tons of carbon dioxide per year — the equivalent of 1,270,000 vehicles driven for a year —will help the state meet its climate goals. But it will also cause approximately 450 workers to lose their jobs. To soften that blow, the law requires Public Service Company of New Mexico (PNM), the plant’s majority owner, to spend about $40 million on retraining and helping San Juan County diversify its economy.

Now the future of the plan is uncertain. After PNM submitted its plans in July, the commission made an unusual call: It decided to evaluate the plant closure and financing proposals under an old PNM case that predated the new law. In effect, that allows the commission to sidestep the Energy Transition Act.

“What the PRC is doing is way off the rails,” says Steve Michel, an attorney with Western Resource Advocates, an environmental organization that helped shape the act. “The commission has never been as dysfunctional as it is now.”

Espinoza declined to be interviewed about the Energy Transition Act, saying she can’t discuss a pending case. Becenti-Aguilar and Byrd did not respond to requests for comment.

Commissioner Stephen Fischmann, elected last fall, acknowledged the commission should be doing more to advance clean energy and keep up with the fast-changing renewables industry.

“With power generation and distribution, there’s so many new technologies coming on board that are developing fast — costs are coming down fast, options are exploding,” he says. “I do believe the agency needs to be far more forward thinking. We shouldn’t be reactive, we should be proactive.”

The pressure to move the state’s energy transition forward is heightened this week as kids in New Mexico and across the world hold climate strikes timed to coincide with the UN Climate Action Summit. Artemisio Romero y Carver, who will be among about 2,000 kids attending the Santa Fe strike on Friday, fears that if elected officials don’t double down now, children in his generation will be the ones who suffer most.

The UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, a group of the world’s top climate scientists, issued a report last October warning that to avert the worst consequences of climate change, including an increase in deaths from malnutrition, heat stress and disease, countries must drastically cut emissions by 2030.

“Honestly the thing that scares me the most is the idea that I might not live past 50, that I might never have kids, that I won’t ever really be able to create a family,” says Romero y Carver, 16, a student at the New Mexico School for the Arts.

A fraught agency

Just as the state is poised to act aggressively on climate change, allegations of a lack of expertise within the commission are raising questions about its competency. A broad mandate to regulate some of the state’s most complex industries, including utilities and telecommunications, means that many commissioners enter the job underqualified. A 2011 report by the nonpartisan think tank Think New Mexico concluded that “the PRC now has the broadest jurisdiction of any state utility regulatory agency in the nation, and PRC commissioners tend to be less qualified than their peers in other states.”

Eight years later, Michel says the qualification issue remains a problem. Commissioners have to log 32 hours of continuing education each year to help ensure they keep up with the fast-changing industries within their purview. Their recent actions show that some are still poorly informed, he says.

While a well-qualified staff can help commissioners make better decisions, multiple vacancies have left the agency lacking in expertise. As of September, 34 PRC staff positions were vacant, including chief of staff and three jobs in the utility division, according to data from the New Mexico Sunshine Portal and the PRC employee directory. Some positions have gone unfilled for six months or more.

“Our utilities are starting to say, ‘yeah, we need to transition more and more to clean energy resources.’ But you have a staff that’s been gutted; there are three or four individuals who are doing all the work,” says a former commission staffer who asked to remain anonymous. “And they don’t have modern thinking.”

A May 2017 analysis of the agency by the National Association of Regulatory Utility Commissioners found that a lack of expertise and understaffing was hurting the PRC’s effectiveness. Its “meager staff” is “a serious problem that makes it difficult for commissioners to make well-informed decisions,” according to the report. Internal politics, low morale and a reluctance among staff to assert their views “in fear of retaliation” add to the dysfunction, the report noted.

Ultimately, the responsibility for good decision-making lies with the elected body, says Commissioner Cynthia Hall, who was elected in 2016. “Notwithstanding the importance of having a really top-notch staff, commissioners should be the smartest people in the room.”

Hall says she sought office in large part because of the problems she observed while serving on the commission’s general counsel staff from 2008 to 2010.

“I felt the role had become urgent in plotting a course for our state to enable a lot more use of renewable energy, given that that was going to be a very important way to combat the worst effects of climate change.”

Problematic decisions

The 23-year-old PRC has a long history of controversy. Over the years, various commissioners have been charged with ethics violations, sexual harassment and misusing public campaign funds.

The current commission has weathered criticisms of infighting and political maneuvering. But it’s the body’s recent record that has renewable energy advocates concerned.

In a controversial case earlier this year, the commissioners ordered PNM to charge Facebook for nearly half the cost of a 45-mile, $85 million transmission line that would allow the company’s new data center in Los Lunas to tap 166 megawatts of power from the La Joya wind farm in Encino. The decision rankled energy experts and state officials, who said it was wrong to charge one user for a project that would also benefit others. The PRC had already approved the contract for the project.

“If New Mexico does not keep all of the promises made to this company, we may not have the opportunity to land another project of this caliber for years,” wrote Economic Development Secretary Alicia Keyes and Energy, Minerals and Natural Resources Secretary Sarah Cottrell Propst in an April 2019 letter to the commission. “There is no bigger ‘red flag’ to a site selector or business executive than failing to follow through on an agreement.” The commission is reconsidering its decision.

Renewable energy advocates were also dismayed by the commission’s rejection of a proposal for New Mexico’s portion of the 520-mile SunZia Southwest Transmission Project. The line was designed to deliver power from a wind farm near Corona, which the PRC approved separately, to California; Arizona regulators had already approved their share of the project.

The price of delay

Dismayed by the commission’s handling of the Energy Transition Act proposals, Western Resource Advocates has taken the PRC to state Supreme Court. The group seeks to force the commission to comply with the law.

Any delay in the law’s implementation could place at risk not only help for workers, but also three existing contracts for new renewable projects in northwest New Mexico.

“There are so many false starts that you can tolerate before things start to unravel, and the consequences could be severe for everybody,” Michel says.

With the San Juan plant set to close in two years, replacement power sources need to be built quickly, so timely approvals are essential, says Ron Darnell, PNM Senior Vice President for Public Policy. Further adding to the urgency, the days are numbered for federal tax incentives for renewables, which helped spur bids for the replacement power. At the end of this year, the credit for wind facilities expires and the credit for commercial solar projects decreases.

Workers at the neighboring San Juan coal mine, which exclusively supplies the plant, may be the first to suffer. The 40-year-old San Juan Generating Station is scheduled to close in 2022, and after next year it will start running on stockpiled coal, says PNM spokesperson Ray Sandoval.

“One of the things we’re worried about is when those miners lose their jobs in July, without the [approved] financing order we aren’t going to be able to provide training for those workers,” he says.

Searchlight New Mexico is a non-partisan, nonprofit news organization dedicated to investigative reporting and innovative data journalism in New Mexico.