Two years ago, Edie Steinhoff, a marketing and publications coordinator at the New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology, was completing a do-it-yourself project when she lost all of her fingers on her left hand.

“I was remodeling my kitchen, and I was using the table saw, and I’m not sure exactly what happened, but it hit a knot or something, and I raised my hand, and all my fingers were gone,” Steinhoff said. “My reaction was, ‘This is going to be a life changer.'”

As a result of the injury, she said she was no longer able to complete everyday actions, such as hanging a photograph or using a standard computer keyboard like she used to.

She said a donor, who asked to remain anonymous, heard about the accident and donated $50,000 to create a robotic hand for her.

Steinhoff said she wanted the device to be created at New Mexico Tech, because “this is what Techies do. This is what they’re experts at, and this is their passion. If any good could come out of this, it would be working with the students here.”

Dr. David Grow, an associate professor at New Mexico Tech and the director of the university’s Robotic Interfaces Lab, created the Steinhoff Prosthetic Research Initiative, also called the SPRI Hand Project, in an effort to help Steinhoff regain mobility.

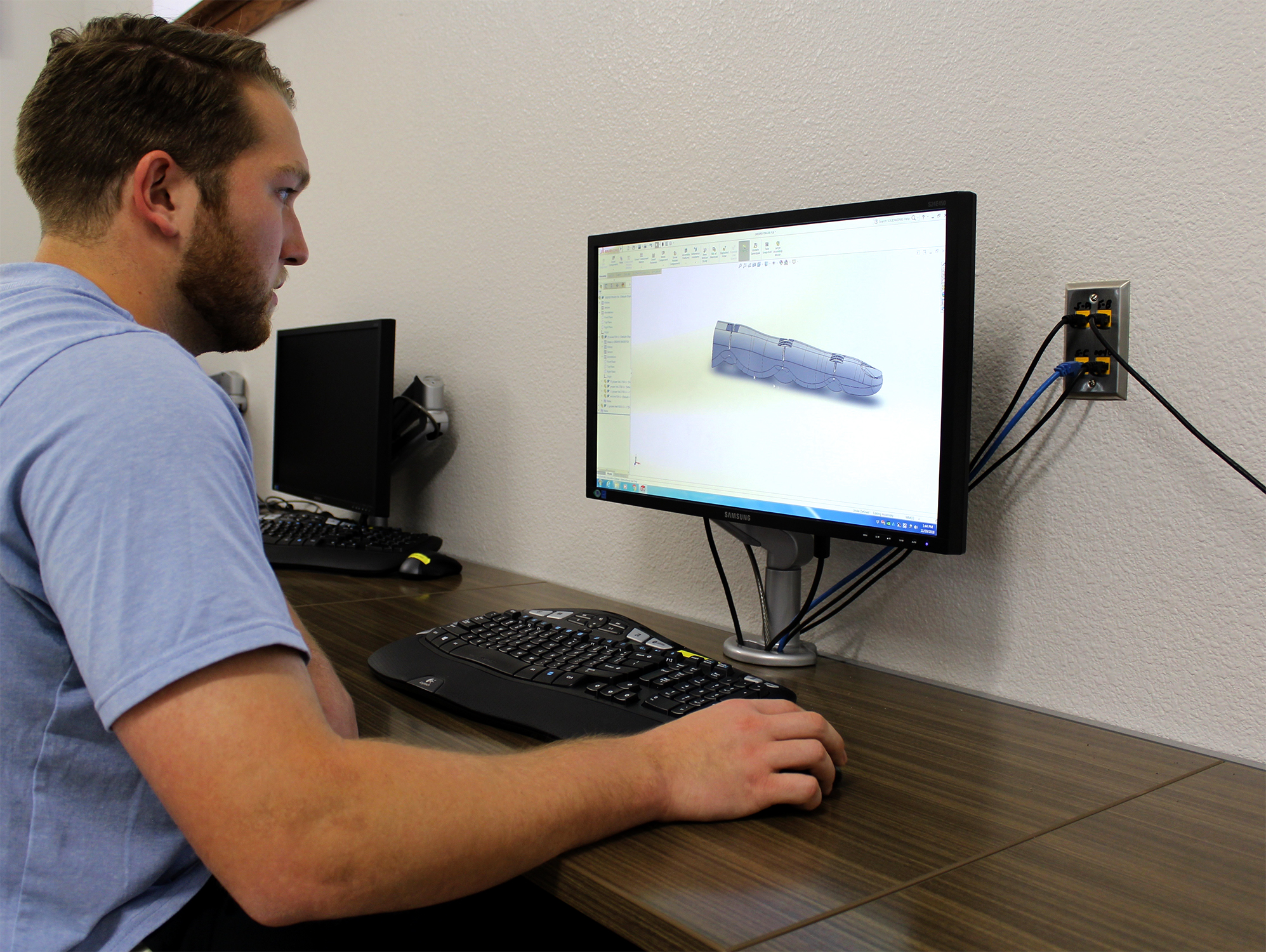

At first, student volunteers ran the project, working with him to construct prototypes, Grow said. The following summer the team started to build, and in the fall of 2017 an undergraduate engineering student design team began working on the project.

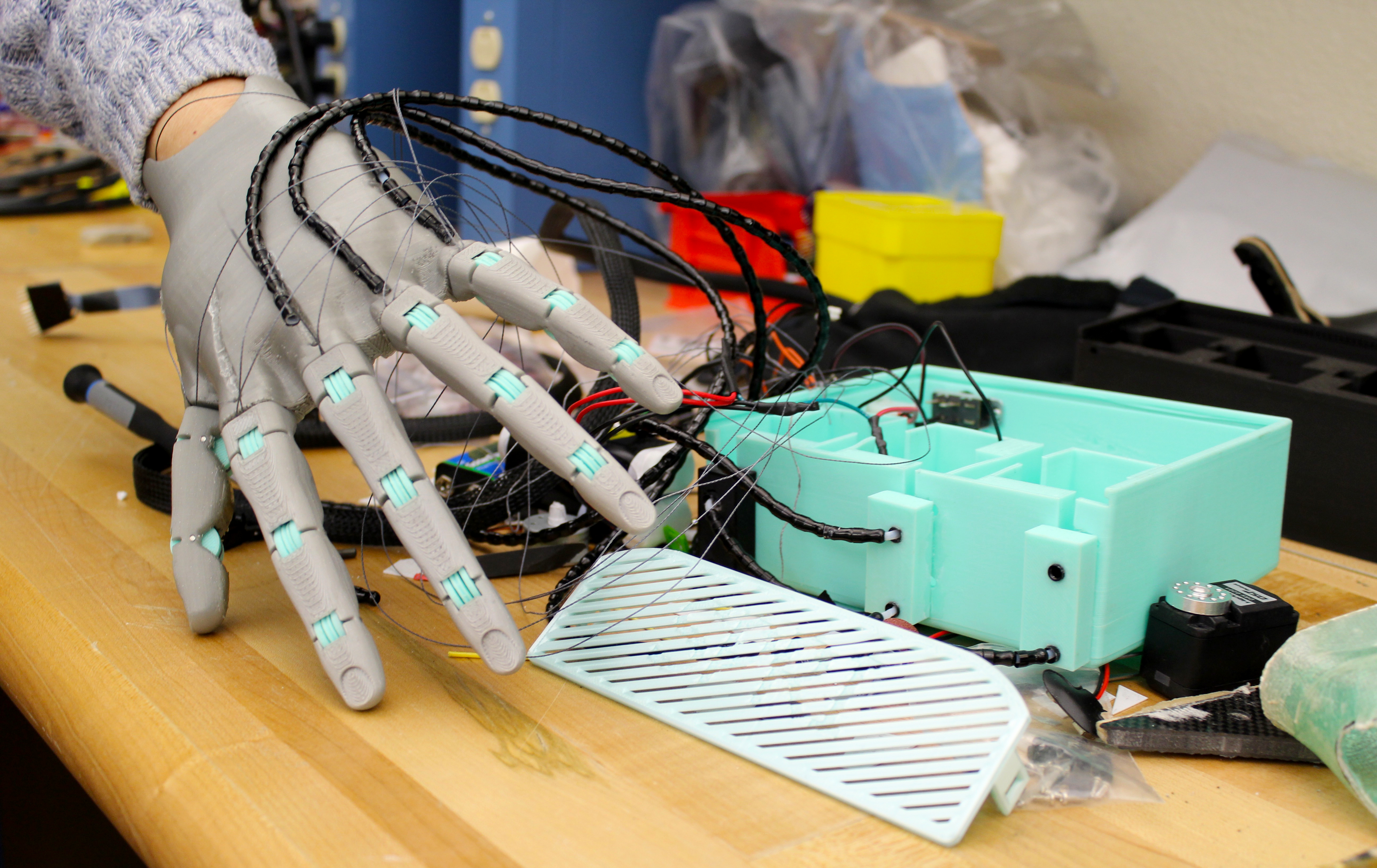

Today, two undergraduate design teams and three graduate students are working on the SPRI Hand Project, he said. The students use a traditional machine shop on campus and often use a 3-D printer for small parts. The printer allows them to create pieces quickly, sometimes creating multiple versions of one part in a single day as they determine what would work best for the device.

He said the group also works with Dr. Christina Salas and Dr. Deana Mercer from the University of New Mexico’s Department of Orthopedics, as well as the Hanger Clinic, which has multiple locations in Albuquerque.

Steinhoff’s office is located near the Robotic Interfaces Lab, which gives students the opportunity to ask her for feedback, Grow said. She attends a few research meetings as well.

“Edie’s involvement in the project remains very significant…I think, often engineers go about solving the wrong problem,” he said. “We think we know what the problem is, and we start working on it, and it’s only when we talk to customers or clinicians that we realize that we kind of had the wrong idea, so having Edie there has really helped us stay on track.”

Brendan O’Brien is a senior mechanical engineering student at New Mexico Tech and the current team leader for the SPRI Hand Project. He said, in previous semesters, the design team focused on creating prototypes, but this semester, the group is focusing on comfort for Steinhoff.

“The project is a highlight in school,” he said. “I’m getting to work with robotics and getting to hopefully help someone gain back daily functions.”

However, the biggest highlight for him was during a design conference at the end of the last school year, he said.

During the conference, the team “actually fitted the first prototype on Edie and got to see her with it on, and it functioned a bit for her…You can see it testing on a workbench, but when it’s on the actual user, it’s pretty exciting,” O’Brien said.

Steinhoff said the accident has affected her in a variety of ways.

“It’s the little things though that surprise me,” she said. “I went out with a friend for dinner, and I realized I can’t cut my meat. ‘Would you cut my meat for me?’ And I felt silly for not realizing it, but things like that just come up all the time.”

Steinhoff said she hopes the SPRI Hand Project will help her complete some of her daily tasks once again.

“My biggest thing is to be able to pinch something, to pick up a piece of paper, to hold a nail, to hold a fork, so I can cut my meat,” she said. “I don’t expect to have one hundred percent use of my hand like I used to, but just to be able to do common things: button a button, zip a zipper. That’s what I hope for.”

Grow said the group is working on various devices for Steinhoff’s everyday use.

“One of the devices is very simple and kind of primitive, but it’s something that we hope she can use on a daily basis right away,” he said, adding that the team already has a few prototypes for a higher-tech version. However the higher-tech device is still being updated on the workbench.

“For the more sophisticated device, the way Edie controls it is actually by flexing the muscles that used to move her finger,” he said. “So the surgery that was done on her was done in a way where the tendons still attach to bone.

And so she’s able to flex those muscles — the muscles that flex and extend the fingers — and there’s a band of sensors that goes around her forearm, and so the current strategy for controlling the device is that that band is picking up on the signals from her muscle movement.”

Steinhoff has “trained” the device several times, Grow said. In doing so, she offers the group additional data about once every month.

“We can use her opposite, or unaffected arm, and by measuring the pressure pattern of the forearm and associating that with the movement of her in-tact fingers, we’re learning how to map that onto her affected hand,” he said.

When complete, the project may not only help Steinhoff, but also many others.

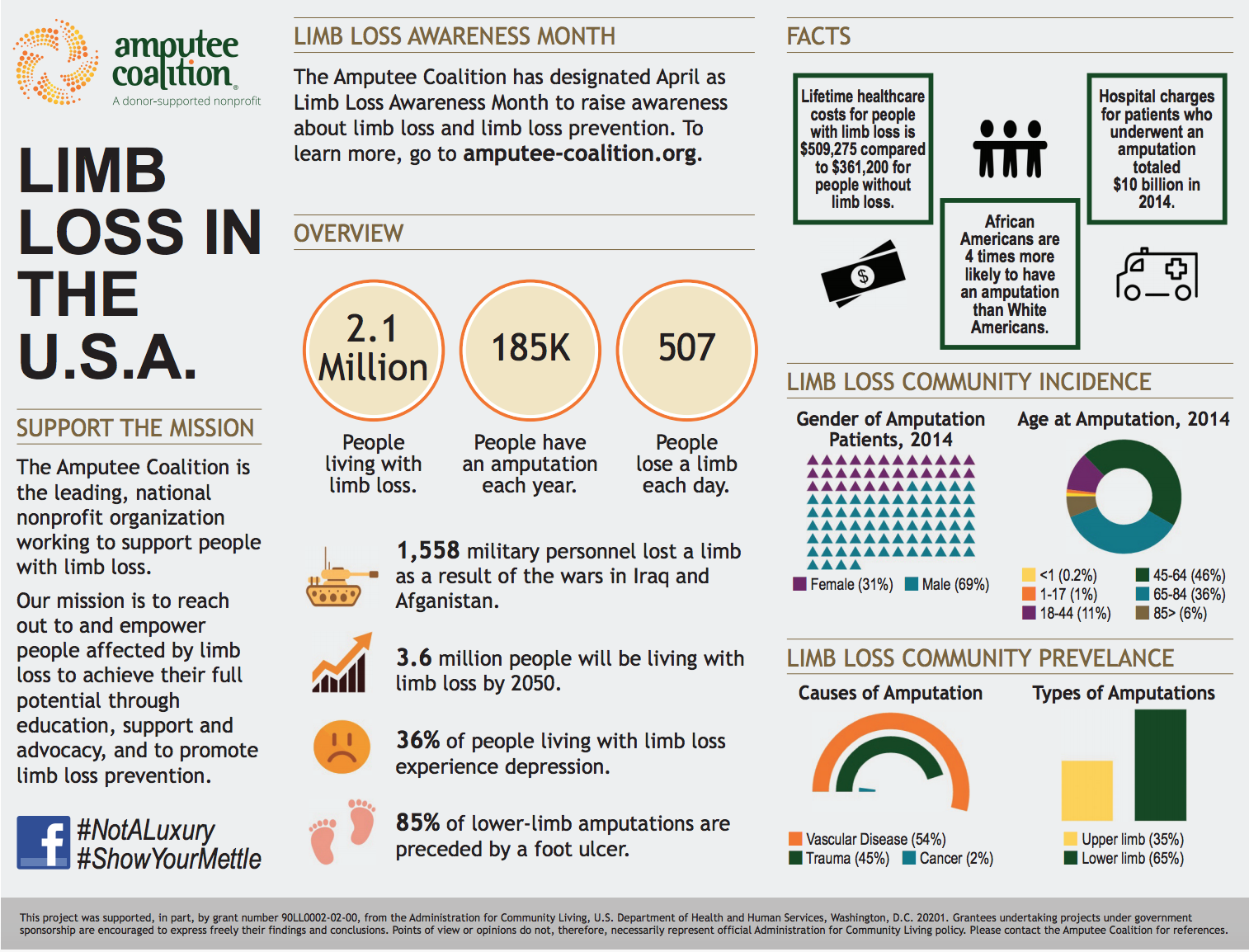

There are roughly 2.1 million people in the United States living with limb loss, according to the Amputee Coalition. When it comes to healthcare costs, people living with limb loss spend about $148,075 more than people who have not experienced limb loss over the course of their lifetime.

Through the use of low cost 3-D printed materials, the SPRI Hand Project may be able to offset those expenses.

The cost of prosthetics can add up quickly. Commercial prosthetics cost between $5,000 to $50,000, whereas 3-D printed prosthetics cost — at most — about $200.

Grow said, prosthetics currently include low-cost devices, which he compared to the hook used by the Peter Pan character, Captain Hook. However, there are also high-end devices that cost much more.

“We’re trying to take some of the high-end technology but package it in a way that the overall prosthetic devices are affordable for most people,” he said.

Steinhoff said the devices’ cost and fit have improved through 3-D printer technology.

“We’re not sure how the business side of this will eventually work,” Grow said. “We’re really just focused on the technology, while trying to keep the technology affordable. It’s possible that this could end up just in a sort of open source format where people could download files, print parts or maybe work with local makers clubs. There really isn’t a serious push now to profit from what we’re doing.”

However, if that point were reached, it could be applied to anyone looking to decrease the cost of their own prosthetics, especially children.

By talking with prosthetists, the group learned that if children who are born requiring a prosthetic are not given that prosthetic early in their development, they tend to never begin using prosthetics effectively, Grow said.

“Especially thinking of places like New Mexico with a rural, dispersed population, relatively low income, if we could make prosthetic devices that were sufficiently useful, inexpensive and available, it could mean the difference between a kid learning, developing their motor skills with a prosthetic or potentially never really benefiting from it,” he said.

One of the two design teams is already working on pediatric software to apply this knowledge to children, he said.

“Edie has consistently said that one of the things she hopes comes out of this is that it benefits other people,” Grow said. “I think, for Edie, that’s one of the things that really helps her see a silver lining in all of this. So while we hope to benefit Edie directly, I think that Edie really has taken joy from seeing the students get engaged and imagining how this is going to benefit other people.”

Although mechanical engineering students — and Grow himself — enjoy solving problems, building and designing, they have also all enjoyed seeing their work immediately benefit someone, he said.

The students working on the project are smart and excited about what they are working on, Steinhoff said, adding that working with them has been “awe-inspiring.”

The university community has also given her a lot of support, Steinhoff said.

“The response from the whole university has been amazing,” she said. “They really treated me like family. I got emails and support, flowers, offer(s) to take care of my pets, to clean my house. I mean, people that I didn’t realize even knew me just came forward and were just so wonderful. It was a humbling experience.”

You can follow Elizabeth Sanchez on Twitter @Beth_A_Sanchez.