A vibrant red couch, soft blankets, comfort food and of course, teddy bears. That is what survivors of domestic violence are greeted by, if they choose to visit Gail Starr’s office after an incident.

Starr is the head nurse and clinical coordinator for Albuquerque’s Sexual Assault Nurse Examiners (SANE). The program shares a building with the Domestic Violence Resource Center (DVRC).

Down the hall, there is medical examination room where survivors will have their injuries photographed for evidence. They are given the opportunity to shower, get a clean set of clothes, and even grab a snack; all services are for free.

“Usually if victims are seeing an advocate with DVRC, they’re kind of at a point where, ‘this was a bad assault; this was scary,’ and they are starting to look for ways to get out,” Starr said.

However, the data shows that even when survivors have had enough, charges are difficult to turn into convictions in New Mexico.

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/314729245″ params=”color=ff5500&auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false” width=”100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

Domestic Violence Convictions Down Despite Steady Number of Cases

In 2015, the New Mexico Department of Health funded its annual analysis of data from the New Mexico Interpersonal Violence Data Central Repository; the report was developed by Betty Caponera. Their most recent report shows that in 2014, law enforcement identified 18,057 domestic violence incidents in New Mexico.

The study found that statewide, the conviction rate for domestic violence cases was an average of 17.5 percent in magistrate courts, down seven percent from 2012. New Mexico district courts held a better average of 38 percent from 2010-2014.

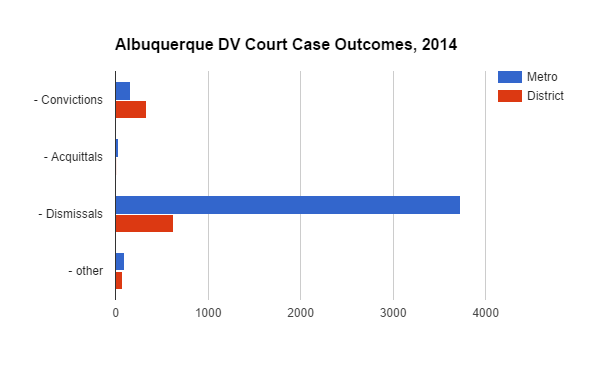

The data shows that in 2014, district courts in Albuquerque had a conviction rate of 32 percent. The metropolitan court had only a three percent conviction rate for domestic violence cases. Out of the 4,019 cases disposed by the metropolitan court, 3,727 cases were dismissed.

When compared to the national average, the metropolitan court doesn’t fare much better.

According to a special report from the federally-funded National Institute of Justice (NIJ) published in 2009, “for most domestic violence cases that do not go to trial, an analysis of 85 domestic violence prosecution studies found an overall conviction rate of 35 percent.”

Lawmen More Likely to be Perpetrators

According to the National Center for Women and Policing, domestic violence happens four times as often in law enforcement families than it does in the general public.

“The number one career path for abusers is law enforcement,” Starr said. “People who want to dominate or control other people go to positions of authority.”

In the Albuquerque Police Department (APD), any domestic violence case involving an officer is investigated by internal affairs. There are no exact numbers on how many times this has happened. However, four high-profile cases have occurred in APD and only one case was investigated by the internal affairs department since 2012, according to documents tendered by APD in response to an IPRA request. APD did not respond to request for comment as to why only one case was investigated. All of these cases were eventually dismissed in court.

No APD officer has lost his or her job because of a domestic violence incident. One officer was placed on administrative assignment, but another remains as a patrol officer. Other officers have left the department for unrelated reasons according to department reports.

APD did not respond to request for comment on these policies or statistics.

Why aren’t offenders convicted?

Starr says domestic violence cases are very difficult to get through jury trials because of lack of evidence, sympathy, and credibility. There are often no witnesses in domestic violence incidents, and survivors might even deny the abuse out of fear of reprisal.

The NIJ report says that survivors’ fear of testifying is the most common reason not to go through with prosecution.

“Although studies have found multiple reasons for victim opposition to prosecution, fear is among the leading reasons expressed by victims. Fear of the abuser is first and foremost, followed by fear of testifying in court,” it reads.

Kelsi Howell, case manager for DVRC, says outsiders don’t consider the plethora of issues that come with leaving an abuser.

“People aren’t as sympathetic to domestic violence because the victim has a choice to leave. They don’t realize how hard it is… what barriers are in place, the fear, the lack of housing… financial support… We’ve had several people just say, ‘it was so much easier when I was with my partner; might as well just go back to being beaten every day,’” she said.

Starr says that 44 percent of SANE’s patients have been strangled, and that increases their willingness to seek help because of the potential lethality. Because it is not specified in New Mexico Statutes, strangulation is usually charged as misdemeanor battery or treated as a means to commit murder. Where the majority of other states have legislated a felony charge of strangulation, whether it is lethal or not, here in New Mexico it does not carry its own charge.

“New Mexico is one of nine states that does not have an official felony offense for strangulation,” she said.

Furthermore, arrests don’t always equal significant lock-up time.

“There’s a quick turnaround rate for someone who has been arrested,” Howell said.

Advocates Attempt to Explain Roots of Domestic Violence

As advocates for domestic violence survivors, specialists have close to an insider perspective on the issue.When asked about what causes domestic violence, they pointed to society’s patriarchal structure and abusers’ internal battles.

Cole Carvour, a training and development specialist at the University of New Mexico (UNM)’s Lobo Respect Advocacy Center, says abusers have usually been exposed to the behavior they’re emulating.

“Domestic violence perpetrators have often experienced or witnessed this type of violence at some point in their life,” he said.

Starr says abusers don’t often see themselves as the bad guy.

“An abuser has a hole inside that they need to have filled… they think that by manipulating or hurting somebody, they can feel better about themselves, and it somehow justifies [it],” she said.

According to Carvour, a patriarchal society, an emphasis on masculinity, and victim blaming also play into the issue. Starr says the culture doesn’t say domestic violence is important.

“Look at Russia, they just reversed all of their DV legislation and said, ‘women, be proud of your bruises– you have a real man,’” Starr said.

Domestic Violence Reports up at UNM

According to UNM’s annual Clery report, there was a rise in domestic violence incidents reported by UNM students from 2013-2015. The number of incidents in 2015 was 21, up from 15 the year before.

“It happens more frequently than people would assume. Even having worked at a service provider outside of campus, I was surprised by how often I do get DV cases on campus,” Carvour said.

Broaching the issue of domestic violence on campus, and in the community, involves both outreach and education.

“Prevention is a really old-school way of looking at domestic violence. Risk reduction… [isn’t a] macro solution. We want to be reaching out to folks and teaching them… how to not be a perpetrator in an unhealthy relationship,” Carvour said.

For the safety of survivors, addressing the problem early could prevent potential lethal escalation.

“The cycle [of abuse] continues until someone chooses to break it, and sadly sometimes it’s broken by someone dying,” Howell said.